Kodak is a publicly traded company, which means they have to put out an annual report for shareholders that goes into microscopic detail about the company’s assets and liabilities that may affect the stock price in the coming year.

As film photographers, we gotta know if the technology and cameras we’re spending thousands of dollars on are going to be more than just paperweights in just a couple of years.

Because if Kodak fails, it’s not just Kodak — it’s also Lomography, CineStill, Film Photography Project, Santacolor, and maybe even Fuji, which is putting out film with a new Made in the USA label. In 2023, it’s safe to say Kodak is the primary manufacturƒer of color film. Fuji intends to restart production, and there is also potential for Orwo, and a few other indie manufacturers to make it big. But the remaining manufacturers only make black and white film.

Kodak used to be one of the most profitable companies in the world, having once employed up to 120,000 people worldwide. Kodak was also traded on the S&P 500 index fund from the fund’s inception in 1957. People who have never shot Kodak film know the brand from the iconic bright yellow logo, and viral ad campaigns like the Kodak Moment. But Kodak stopped making money in the 2000s with the rise of digital photography.

Kodak went bankrupt in 2012 after losing billions and had to restructure the entire business to keep the lights on. Kodak sold its digital kiosk, camera, film chemical, paper production, and film sales divisions to the UK Kodak Pension Plan to resolve a 2.8 billion dollar claim against the company. That sale split the company into two distinct entities: Kodak Alaris, and Eastman Kodak.

In this article, we’re talking about Eastman Kodak, which is the company that makes the film in Rochester New York, along with various other ventures.

Kodak Alaris makes money by purchasing the film from Eastman Kodak, and then marking it up and distributing it across the world.

In the 2022 annual report, Kodak announces everything, from how much money they made raising film prices, to how much debt they still have, and how much money they expect to lose fighting lawsuits in New York and Brazil.

So will Kodak be able to continue running as a profitable company? And how close are they really to shutting down for good? Is Kodak Okay?

How much money Kodak Made in 2022

In 2022, Kodak made 1.205 billion USD. They made money in 4 categories: Traditional Printing, Digital Printing, Advanced Materials and Chemicals, Branding, and then they make some small revenue from other, non-reportable sectors.

Traditional Printing makes up the bulk of Kodak’s sales at just under 60% of the total business. Traditional Printing includes selling printers, inks, Sonora Process-Free plates, packaging, and other materials for consumer and professional printing presses. The remaining slices of the pie are 227 million from digital printing, 17 million from selling their brand name, and 16 million from “other.”

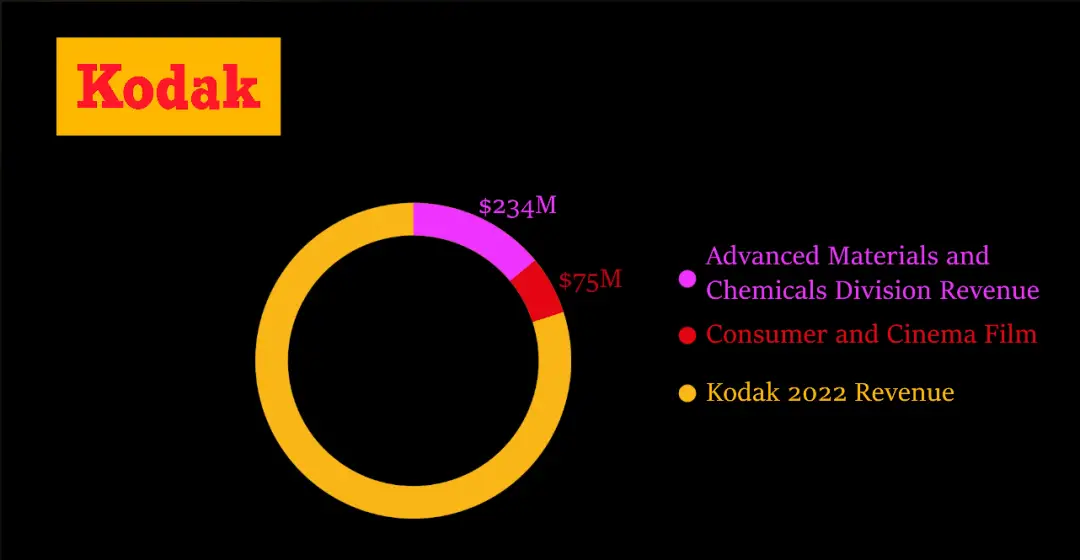

Film production falls under the Advanced Materials and Chemicals division, which is the most forward-thinking division in Kodak’s portfolio. But in 2022, Advanced Materials and Chemicals made just 234 million, or 20% of Kodak’s total revenue.

Consumer film production (the film sold to Kodak Alaris) accounted for just $75 million, or a grand total of 6% of Eastman Kodak’s revenue last year, with a 15 million dollar increase in those profits directly attributed to “improved” pricing. Film produced for cinema, and other manufacturers like CineStill, Lomography, and other manufacturers that resell film accounted accounted for $105 million of Kodak’s total net sales. In total, film sold accounted for $180 million, or 15% of Kodak’s bottom line.

*Correction notice: this article used to say Kodak film made $75 million in total. This was an inaccurate statement.

If that number feels low, here’s why. Eastman Kodak only creates the film. After Eastman Kodak finishes a production run, they sell it to Kodak Alaris, which has been owned by the Pension Protection Fund in the UK since 2020, and is the marketing and distribution middleman who then marks up prices for their service. For reference, Kodak Alaris generated $30 million in revenue from film sales in their financial period ending March 2022, on top of their sales from the Kodak Moments brand, which sells prints from kiosks in stores, as well as online.

The timing of the annual reports is a little ways off, so it’s hard to get a complete picture of the total revenue from selling Kodak film in 2022 — And to add further complexity, Kodak Alaris is technically a private company owned by the Pension Protection Fund in the UK, meaning they’re technically not obliged to give shareholders their entire financial picture the way Eastman Kodak does, but we may still see an annual report published in fall 2023 detailing how much they made in the remainder of the year.

Despite what many reports would have you believe Kodak’s business comes from a surprisingly broad range of industries. They create products like light-blocking fibers, unregulated Key Starter Materials, or KSMs for pharmaceutical companies, as well as materials to print circuit boards and build batteries. They also produce inkjet printers, software for printing companies, as well as large-scale press printers and packaging machines for books, magazines, and newspaper publishers. Over its 130 years in the business, Kodak has developed a staggering 79,000 patents, which it uses to protect its IP and generate revenue.

But where things start to get complicated are the costs of doing business. If you’ve heard Kodak is hanging on by a thread, it kind of is, and here’s how thin it’s getting. To make that $1.205 billion in revenue in 2022, Kodak spent $1.035 billion. That includes everything from taxes, $134 million in wages for over 4,200 employees, construction costs, licensing, raw materials, environmental obligations, court cases, and a lot more. So what Kodak ends up with after all the dust settled is just $26 million dollars.

That means Kodak’s profit margin is 2.2%, which is lower than your average restaurant. Heck, even the bad restaurants and cafes are bringing home a higher profit margin than Kodak. If there were two Subways across the street from each other competing for the same customers, they’d still have a higher profit margin than Kodak. I think you get the point — that profit margin is abysmal.

And this is during the height of the film resurgence when Leica, Pentax, and MiNT are developing new film cameras, and hipsters, nerds, and deep-pocketed enthusiasts are willing to put down premium money so that they can work harder for the experience of creating images on film. Even the most ardent supporters of film know that it’s more about the experience than the quality of the images created — and I’m saying this as a self-professed lover of the medium. Film is awesome, it’s fun, and it’s an amazing way to diversify your skills, and learn more about photography. But film just isn’t as good as digital photography for professional photos.

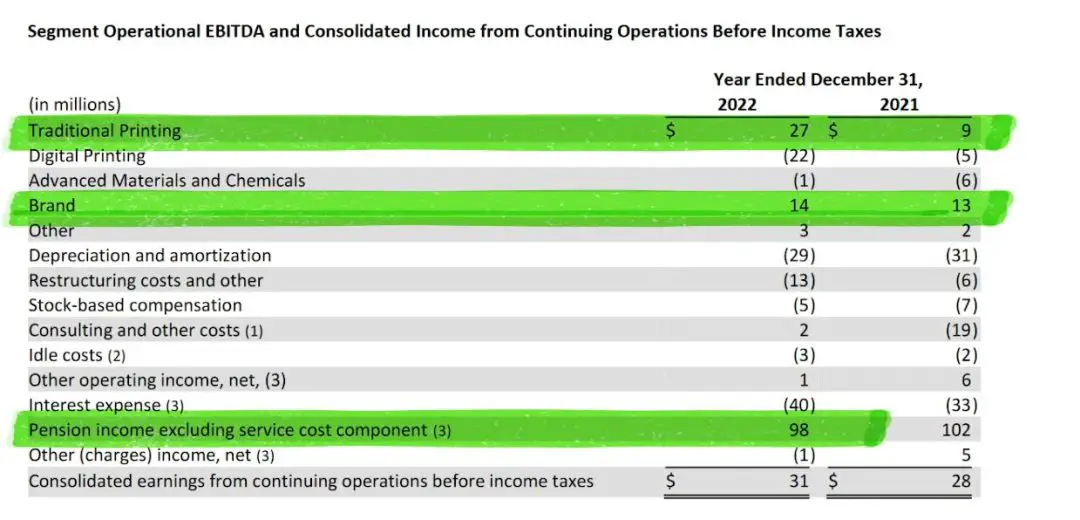

When drilling deep into the report, Kodak noted that after all costs were considered, the Advanced Materials and Chemicals division actually lost $1 million in 2022, which is up from a $6 million loss in 2021. Kodak benefitted from increased prices, and higher volumes of motion picture film, but lost money from increased manufacturing costs and investments in the sector.

The most profitable ventures for the company after accounting for costs, were selling the brand name, for $14 million, traditional printing, which pulled in $27 million, and $98 million in extra income generated by Eastman Kodak’s multi-billion dollar pension fund. This means in 2022, Kodak made more money operating as a hedge fund than it did from any other segment of its physical business.

And just for comparison, Kodak’s peak revenue was over $16 billion in 1996, which translates to over 31 billion today when accounting for inflation. Consumer photography started to hit its peak as electronic cameras made photography faster, easier, and cheaper than ever before, developing kiosks were more common than Starbucks and Dunkin Donuts combined. Kodak was pretty much the only game in town, and everybody was playing. Kodak today makes less than 8% of what it did during its 1996 peak.

So let’s get into why Kodak is doing profit margins that are barely better than a gas station.

Bankruptcy Breaks Kodak into Eastman Kodak and Kodak Alaris

When Kodak went bankrupt in 2012, they took on a massive 895 million restructuring loan and sold off the easy parts of its business to the UK Kodak Pension Plan to settle a $2.8 billion dollar claim to keep the pension dollars flowing.

To resolve that dispute, Eastman Kodak transferred the film distribution sector, as well as manufacturing of photo chemicals, light-sensitive Kodak paper, cameras, frames, and online photo service businesses (which they renamed Kodak Alaris), to the UK Pension Plan.

Eastman Kodak held onto the most specialized services, like producing film, chemicals, coatings, and other materials that couldn’t be done without 100 years of experience. They scrapped most of their plants, and laid off most of their staff, throwing away generations of knowledge and machinery that are simply not replaceable on a $26 million-dollar budget.

In 2020, Kodak Alaris was transferred from the Kodak UK Pension Fund to the United Kingdom’s Pension Protection Fund, which is a governmental organization designed to save pension funds from bankrupt companies. When the Pension Protection Fund took over Kodak Alaris to secure payments for the pensioners, it decided it would be more profitable to brake Alaris apart, and sold the photochemical, paper, and display division to their Chinese distributor, Sinopromise.

If you’ve been developing film at home before 2020, then you likely saw new packaging wreak havoc on the longevity of Kodak film chemicals during the pandemic. Many film photographers around the world reported getting blank rolls due to developers that had exhausted before they were mixed. This problem was caused by SinoPromise trying out inferior packaging materials that didn’t keep the chemicals shelf safe.

Now, in 2023, the Pension Protection Fund plans to sell the remaining parts of Kodak Alaris starting in 2023 — which could potentionally mean more price hikes in the future.

In the USA, the pension plan was a little better stocked up. Over the company’s 130-year history, Kodak built an investment portfolio for its North American pension fund with a combined fair value worth $4.2 billion in 2022. This is made up of real estate, private equity, and hedge funds. Through these investments, the fund produces enough profit to pay the expected pension rate. In 2023, Kodak expects to pay 333 million in international pension benefits, with the amount decreasing by approximately 10% each year thereafter.

After all was said and done, this pension plan had an extra $98 million in revenues transferred to Eastman Kodak in 2022, which it’s safe to say was what kept the company in the black.

The pension fund is not actually controlled by Kodak, and it’s not an asset on the company’s balance sheet — the pension fund is a separate entity that has a fiduciary duty to the pension holders, and sometimes a little extra profit may be put back into Kodak’s piggy bank. But it’s not like Kodak can just dip into the pension fund whenever they want for pizza parties (or whatever billion-dollar multinationals do).

Kodak’s Debt

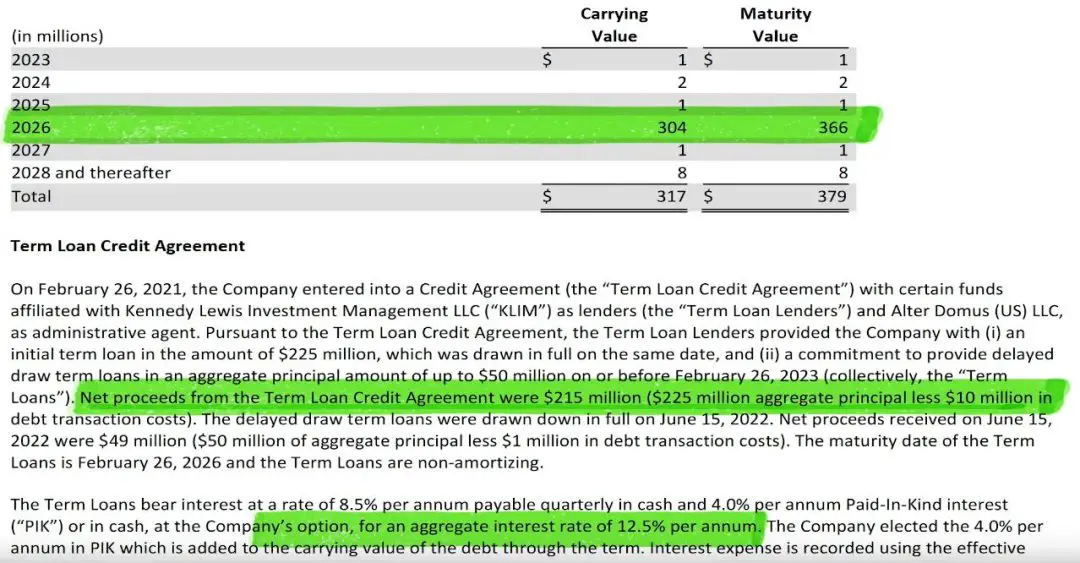

In terms of debt, Kodak owes $225 million dollars from a loan they took out in 2021, which was likely a renegotiation of the original 895 million restructuring debt. This loan incurs a staggering 12.5% interest per annum and matures into a $366 million dollar loan by 2026. Until the maturity date, Kodak is just paying off the interest along with a small amount of the principal or fees, amounting to 40 million in 2022. That means the company will need to find a way to pay off the entire $366 million dollars in 2026 or renegotiate the terms.

For the duration of the loan, Kodak must maintain a minimum of unrestricted liquidity (or cash on hand) of $80 million dollars, or they risk having the bank call in the loan prematurely. It’s safe to say if that happened, it would mean a fire sale of company assets.

The cause for concern is Kodak’s significant liquidity drawdown. In 2021, Kodak had a healthy, unrestricted $250 million in cash, but in 2022, they drew that fund down to just 150 million in the US, leaving very little room for error. On a scale like Kodak’s, it doesn’t take much to spend $70 million dollars — the company already burns roughly $3 million dollars every day.

When accounting for their large drawdown of the unrestricted cash, Kodak’s blamed it on the same usual messages we’ve heard time and time again. The report said:

“Kodak is experiencing negative cash flows due to supply chain disruptions, shortages in materials and labor, increased labor, commodity, and distribution costs, and a slowdown in customer demand related to global economic conditions. The economic uncertainty surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, the current inflationary environment, and other global events represents an additional element of complexity in Kodak’s plans to return to sustainable positive cash flow.”

But of course, that’s not all. If it was just the debt, the cash flow issue, and recovering from the company’s split, Kodak would still be in a tough place. But Kodak is also going to court. Kodak is facing a few different cases, including a tax and labor dispute in Brazil, and multiple insider trading lawsuits taking place in New York.

For the Brazillian case, there isn’t much information available online — you can’t find it with a Google search, (even when searching in Portuguese) but there is a small mention of it in the annual report. Kodak states this single lawsuit could cost Kodak up to $116 million dollars, which if that went through tomorrow, would bring Kodak’s liquidity $46 million dollars under their $80 million threshold. Of course, the maximum lawsuit amount is always an over-the-top number. Kodak notes in their report that even though they intend to defend their position vigorously, they expect to lose 6 million in the case.

Now the New York Lawsuits all stem around the 2020 announcement that Kodak would receive a $765 million dollar loan from the United States government to follow Fuji’s lead and invest in manufacturing generic drugs. The ultimate goal was to help produce generic drugs for the Covid 19 Pandemic, though the deal ultimately fell through shortly after when the government started investigating alleged insider trading by Kodak executives around the time the deal was announced.

A class action lawsuit on behalf of shareholders was also filed shortly after the government reneged on the announcement, and the stock price of Kodak tanked. Though that lawsuit was dismissed with prejudice on September 28, 2022 — meaning it cannot be reopened. So Kodak escaped the class action lawsuit, but they’re far from out of the water. Kodak, along with some of the former and current directors are defending themselves in both federal and state courts for breaching Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act, for allegedly breaching fiduciary duty and unjust enrichment resulting from stock trades, option grants, and a charitable contribution in the context of the Covid-era pharmaceutical loan announcement. The state court is currently pending, awaiting a resolution in the federal court before it proceeds.

That court case is still active as of December 2022, and at this time, Kodak has not estimated the likelihood of loss in this proceeding.

What does this all mean for Kodak?

The good and bad news is Kodak is not relying on the sale of film to keep them afloat in 2023. Over 130 years of technological advances from being one of the largest companies in the world has granted them an enormous amount of assets that can be used to keep their company afloat and pivot to new ventures, which we’re already seeing. Kodak has a thriving business in the traditional printing sector. And on the side, they’re making batteries, printing circuit boards, creating advanced materials, and investing in manufacturing key starter materials for the pharmaceutical industry.

Most people say that Kodak’s biggest failure was not chasing digital photography. But when you look at the digital photography market in 2023, even the biggest manufacturers are struggling. Canon, Nikon, Fuji, and Sony combined are all spending billions each year chasing small advances in digital photography, hoping that new marketing will make photographers ditch last year’s camera. For example. Canon made 28 billion US in 2022, which is the same amount of money they’ve made year over year since the early 2,000s. When accounting for inflation, that means Canon is making up to 50% less money in 2023 than they did during the aughts — even though they are the dominant camera manufacturer in the world with a broad portfolio of industries. (They made 28 billion in revenue, but only made 1.7 billion after expenses).

Kodak Didn’t Miss the Digital Age — They Just Couldn’t Compete with the iPhone

Most people say Kodak failed because, despite being the company that invented the world’s first digital camera in 1975, they didn’t make the transition to digital photography.

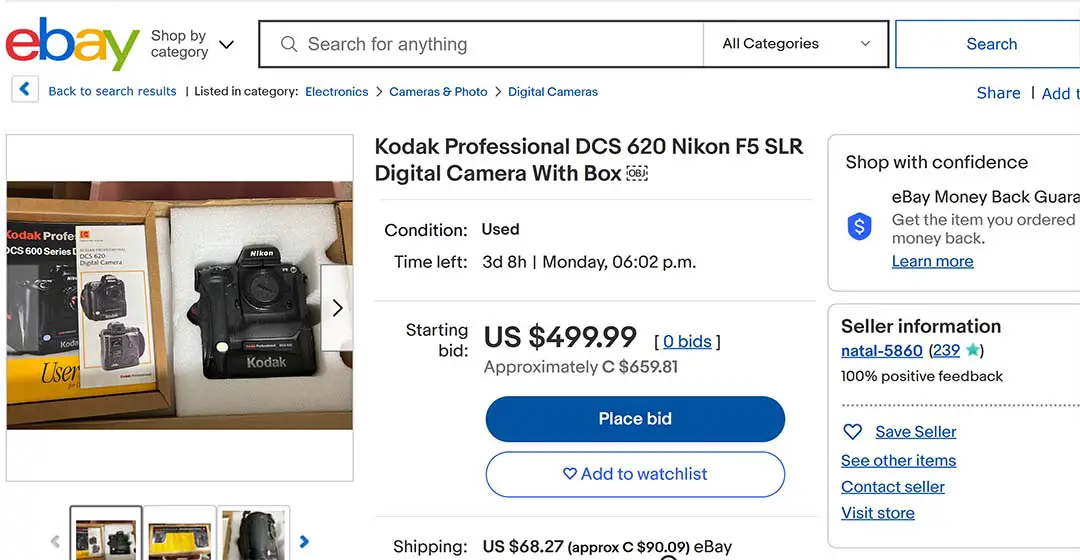

Many people believe Kodak just buried their heads in the sand and let digital photography run them out of business. But that couldn’t be further from the truth. Kodak invented the digital camera in the 1970s and kept slowly developing digital photo technology for the next 20 years until they released their first digital camera, called the Kodak Digital Camera System in the early ’90s!

To make these cameras, Kodak retrofitted Nikon and Canon cameras with digital backs and batteries that look similar to what I’m Back is doing right now. Kodak then sold these digital cameras to the military, the American Press, and other news organizations (costing between $15,000 and $40,000 USD each). Using Nikon and Canon cameras was a sign of Kodak’s camera strategy — Kodak never wanted to invest in creating a system of professional cameras and lenses, so they had to use the ones that already existed to satisfy the professional users of the new digital systems.

Kodak actually paved the way to make digital photography happen, and they made loads of inexpensive digital point-and-shoot cameras for the masses in the 2000s.

While cameras were a big part of Kodak’s strategy, Kodak never tried reaching the professional market. Instead, they focused on the cheap, easy, point-and-shoot cameras (both film and digital) targeting the consumers who didn’t want to learn complicated camera settings, and simply wanted to capture good pictures at parties or family milestones without getting their hands dirty in B&W film developer. That market today is satisfied with their phone cameras.

What made Canon, Nikon, and Fuji different, was they made professional cameras with interchangeable lenses for the market that wants to create high-quality images. These manufacturers today are the only ones making digital cameras that are so good, phones just can’t compete. There is brand recognition from professional photographers creating out-of-this-world photos using this gear, which helps drive sales of high-end, expensive equipment.

Right now, Kodak is making the transitions they need to make to become more viable in the 20th century. By transitioning to creating Key Starter Materials for pharmaceutical companies and investing in batteries and circuit printing, Kodak could be in the right place — even with the $366 million dollar loan coming due in 2026. Kodak’s brand is also still a very valuable asset for them. So long as Kodak continues to only license its brand name on high-quality products, the company will be able to rely on this income for a long time to come.

The biggest hurdle Kodak faces is the risk of a sudden expense bringing their cash on hand below the $80 million threshold. Something simple, like the film production lines going down, losing both court cases at once, or a sudden spike in the cost of raw materials like silver or aluminum could cause major ripples in their finances, and create lasting, year-over-year effects on their bottom line.

Kodak can’t just sell their stock to make up losses like they used to, because stock has a low price and is extremely volatile making it an unattractive asset to trade. It’s safe to say Kodak is taking this problem seriously because they still topped up their liquidity despite earning 12% less in the first quarter of 2023 than Kodak did 2022.

But there is also a lot to look forward to in 2023. For instance, film photography is still surging. And even with the price increases, film only made Kodak $75 million dollars of its total 1.2 billion in revenue — Film is not a big driver of Kodak’s bottom line revenue. Certainly, film is a profitable venture, and it is the venture that provides funding for Kodak’s continued research in their Advanced Materials and Chemicals division, which is the most forward-thinking in Kodak’s entire portfolio. So it’s unlikely that Kodak could simply sell their film production to another company without severely handicapping the advanced materials and chemicals division.

And the fact that Fujifilm is most likely producing their film in Kodak’s factory, (again, there’s no confirmation of this, but it is the most likely scenario) means that Kodak is going to see higher than normal revenues in 2023. Though Kodak’s extra revenues may return to normal if Fuji resumes film manufacturing in Japan.

Here’s why I think Fujifilm is now being made by Kodak. Fuji does have factory facilities in the USA, but they never had a film production line there, instead relying on cheap international shipping across the Pacific Ocean. The fact is, in 2023, Kodak can’t make a new film production line even if they wanted to because it’s way too expensive.

If Fuji wanted to move its production to America, it would incur hundreds of millions of dollars in costs. On top of that, they’d have to train all new staff, pay them higher wages, and overcome new environmental regulations. But for what benefit? Better access to the American market? Maybe slightly better access to raw materials? With the ease and reliability of global shipping at an all-time high, spending hundreds of millions to move their production to America just doesn’t make sense, and wouldn’t pay off for more than 10 years — assuming film is even around that long.

But contracting your film production to another high-end facility ensures the money keeps flowing in without getting Fuji’s hands dirty. And we can see this with the production of goods all over the world. For example, the Sapporo, Heineken, or Guinness you drink doesn’t come from Japan, Holland, or Ireland — they’re contract brewed in your country — potentially even in your state by the big brewers like Labatt or Anheuser Busch. And Fuji has made statements about only supporting the photo industry because of its legacy, not because it turns a profit, or because it matters to its bottom line.

But even with all the advancements Kodak has made, and the potential upside they’re seeing in 2023, Kodak is still just a shell of its former self. The market cap, or the value of all Kodak’s stocks combined is around $400 million, meaning Ryan Reynolds could buy a controlling share of the company just with the proceeds he made from the sale of Mint Mobile, or from his role in the Barbie movie — and he could potentially even take the entire business private if he wanted to.

Do you think Kodak is safe? Are you going to keep buying film and film cameras in 2023 even with the price increases? Let me know down in the comments down below.

By Daren

Daren is a journalist and wedding photographer based in Vancouver, B.C. He’s been taking personal and professional photos on film since 2017 and began developing and printing his own photos after wanting more control than what local labs could offer. Discover his newest publications at Soft Grain Books, or check out the print shop.