One of the big reasons many photographers get into film photography is for medium format. It’s no secret that medium format cameras produce the highest-resolution and quality images on film.

Before recent digital advancements, getting a digital camera that could compete with medium format film would cost well over $10,000, and were usually only used by businesses and studios producing high-end product and fashion photography. But that’s all changing with modern advancements in digital photography, where some new full-frame (35mm equivalent) digital cameras create images with higher resolution, sharpness, and dynamic range than medium format film.

But there’s still something romantic about using medium format film that keeps photographers coming back to (and drooling over) these cameras.

In this guide, we’re going to go over everything there is to know about medium format film photography. Including how to choose your first medium format camera, what kind of film to buy, and perhaps a couple of reasons why you may wish to stick with 35mm.

I’ve used a number of medium format cameras over the years, having used them for personal and professional photography. And there are many things to love about medium format, but it’s not all roses. I’m not going to wax poetic and say it’s the perfect choice for everyone, as I believe there are still many times when 35mm cameras are the best option.

What is medium format?

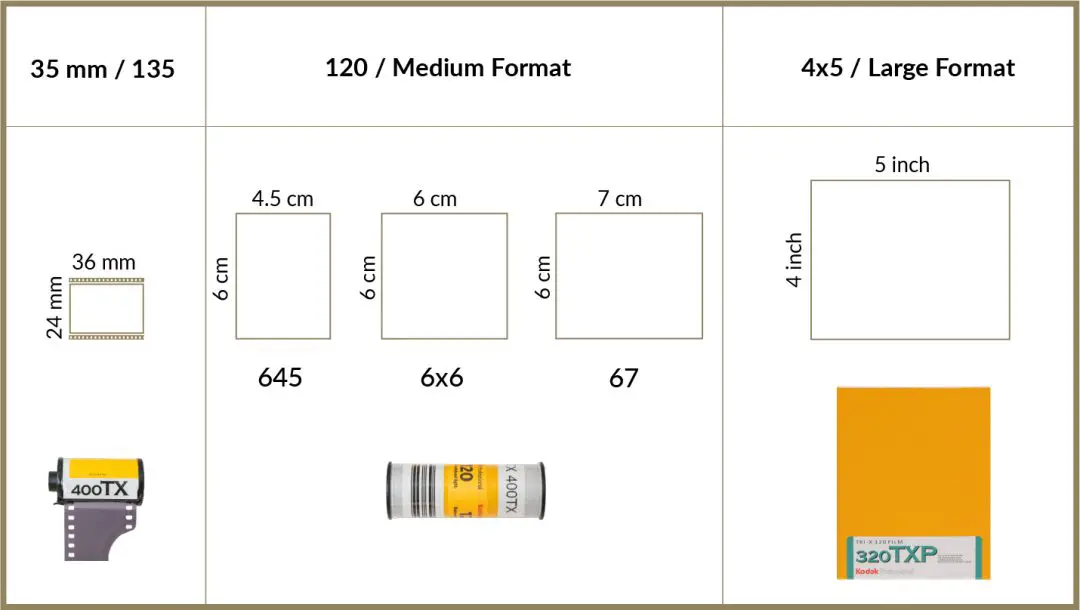

There are four main film sizes that are available to film photographers.

The smallest is 110 film, which is for tiny film cameras that become popular in the 80s and 90s. Because of their small form factor and cheap film, many people had one of these cameras in their glove box in case of a car accident. The only manufacturer currently making 110 film is Lomography.

The next size up is 135 film, better known as 35mm. This is the film you know and love with the sprocket holes on the sides. This is the most popular film format because of the size and the quality cameras that were made for it. You’ll find 35mm all world.

The next size is Medium Format, also known as 120 film. Medium format is a 6cm (2 ¼ inch) wide film that was designed to capture as much detail as possible in a convenient roll format. A single square format image on 120 film is about the same size as 3 35mm images combined.

The largest film type is simply called large format. Large format film is sold in sheets that can be any size between 4×5 inches to even 16×20. These formats are still fairly popular because of the incredible depth of field and resolution they capture. But large format cameras are big, heavy, slow to use, and the film can cost more than $10 for a single image.

A single 8×10 sheet has the same surface area as a roll of 120 film, which has the same surface area as a roll of 35mm. And they are all priced accordingly.

Why shoot medium format film?

There’s an old joke, that with digital photography, you’ll take 2,000 photos and six shots will be awesome. With 35mm film, you’ll take 36 images and six will be awesome. With medium format, you only get 12 photos, but six of them are still going to be fantastic. And there are a number of reasons why.

For one, shooting with larger negatives means you can print larger images without losing detail, or without seeing excessive graininess. However, that’s less of a concern in the digital age when it’s rare to create prints in the darkroom.

As well, because the negatives are so much larger than 35mm, they have a much better exposure latitude. The negatives collect more light and produce images with near-perfect tonal rendition. 35mm film looks contrasty and grainy compared to medium format films, which have smoother tones and create a sharper image overall.

Medium format film sizes

There are three main formats for medium format film cameras. 645, 66, and 67. All of them are the same height, but just have different widths of film, just like the 35mm film cameras that shoot half-frame images.

It’s important to note that every medium format camera will use the same 120 film, regardless of the film format that it shoots in.

Some cameras, like the Holgas, can even have a mask in place that allows them to shoot more frames in a smaller format. Cameras with changeable backs also typically had different backs available to allow the user to choose their image format. Hasselblads and RZ67 cameras, for example, can both shoot in 6×6 or 645 formats, however only the RZ67 can shoot using a 67 back.

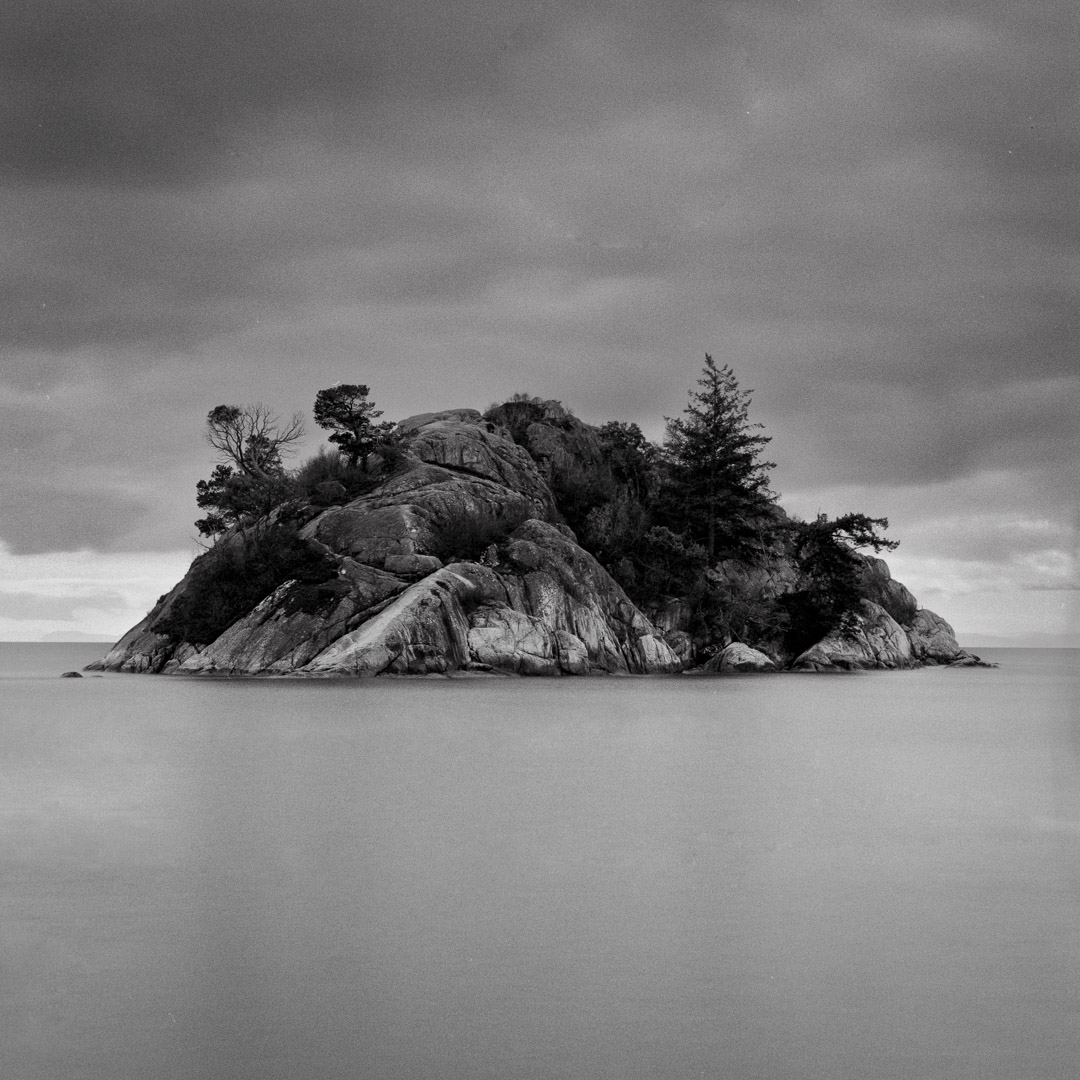

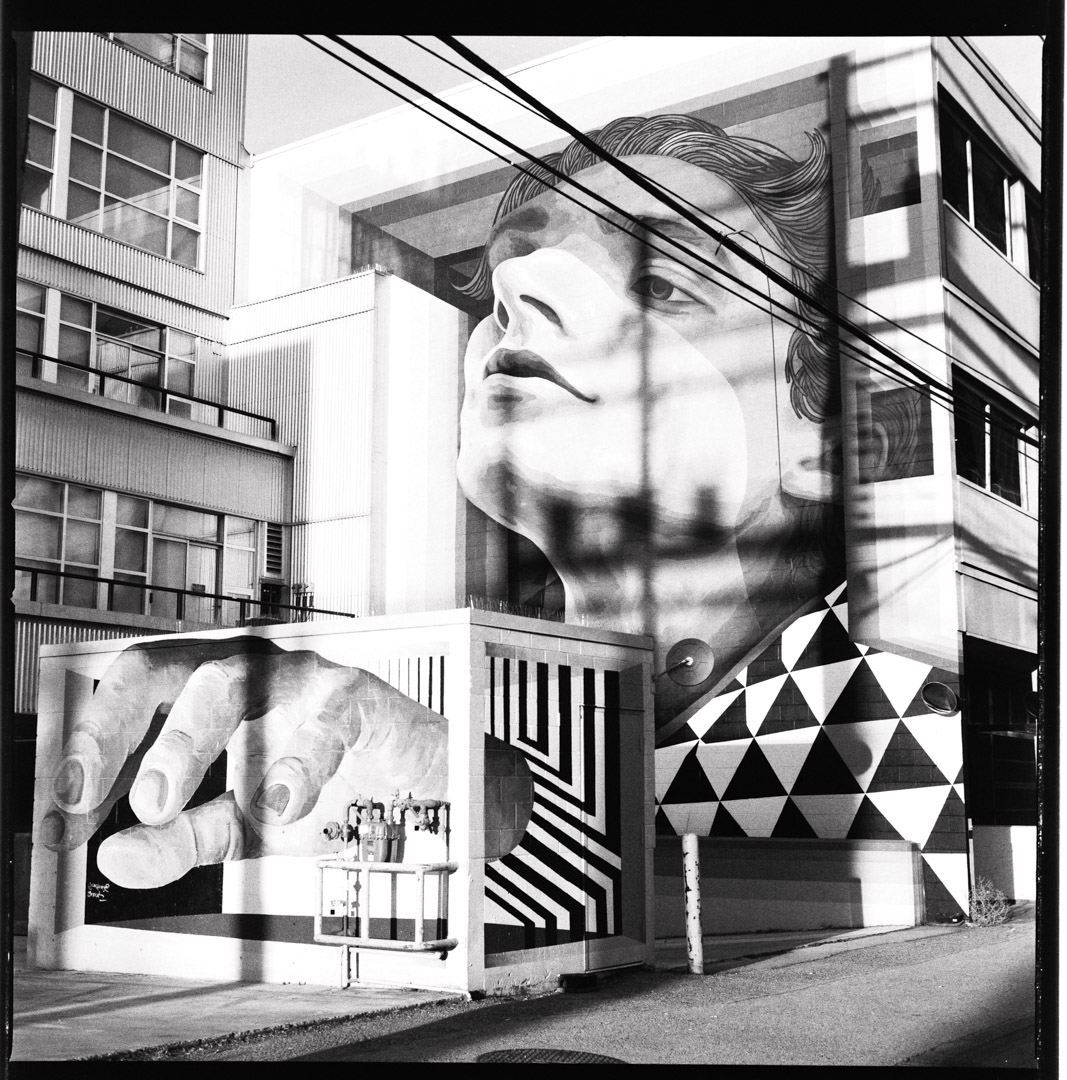

6×6 or square format is the most common. A 6×6 camera gets 12 shots per roll. All TLR cameras, Hasselblads, Kievs, and any camera that doesn’t have either a 645 or a 67 in the name shoots square format images.

The next most popular format is 645, which is a mainstay for wedding and portrait photographers alike because it allows you to squeeze out 3 or 4 extra shots per roll of film when compared to 6×6. The 645 format aspect ratio is also the closest to the 35mm format.

There are also plenty of high-quality 645 cameras on the market, like the Zenza Bronica ETR line, Mamiya 645, Pentax 645, and Contax 645AF.

67 is the largest popular medium format film size. These cameras are prized for the larger film formats, but can only take 10 photos per roll of film. Studio shooters in particular are the biggest fans of the format because of how much larger they’re able to make prints.

There is one other larger format, which is 6×9. Although very few cameras use 6×9 format, because they require progressively larger camera bodies and lenses to create, which means smaller apertures and fewer lens options.

Medium format crop factor and depth of field

The next advantage to come from the size is that images have more pleasing out-of-focus areas, also known as bokeh. Because of the larger image plane, a medium format camera can create more subject separation than a 35mm camera can with the same aperture.

For example, a lens with an f/4 aperture in 6×6 format can capture as much background blur as an f/2.2 lens aperture on 35mm film. This look is prized by portrait, fashion, and wedding photographers.

Crop factor also changes the way focal lengths work. Medium format film photographers will find that equivalent focal-length lenses look much wider on 120 film cameras than they will on 35mm film cameras. This can be a major benefit because it means that wider lenses will have less distortion, which can create straighter architectural lines and more flattering portraits.

Focusing with a medium format camera

These cameras also have large, bright focusing screens that make manual focus an absolute pleasure. Plus, I don’t know why this is, but there’s just no cooler way to view the world than through an acute matte screen of a Hasselblad camera.

For professionals, medium format film cameras are a dream to work with. The biggest problem most photographers have with 35mm film cameras is the size of the focusing screen. It can be difficult to know when your subject is perfectly in focus on 35mm. But the large, bright medium format screens make capturing sharp images a breeze — even at night.

Grain size, sharpness, resolution, and dynamic range

There are a number of considerations when shooting film. No matter which format you use, the film grains will be the same size. The incredible HP5 film is exactly the same, no matter which format you use.

The only difference is the size of the image that is created on top of those grains.

A medium format image will contain many more grains than the same image taken with a 35mm film camera. That means the grains will appear smaller because there are more of them in an equivalent section of the image. This is called resolution.

Medium format film photographs have 3x the resolution of 35mm. And with that extra resolution comes many benefits. Higher resolution images are sharper, have better gradation between the tones (something that you really notice in B&W film).

The only other factor that remains constant between the formats is dynamic range. Medium format film has exactly the same dynamic range as 35mm because the light-gathering ability of the grains themselves do not change with film size.

Can digital cameras compete with medium format film?

The digital world spent almost 20 years trying to match what medium format film is capable of. It’s safe to say that digital medium format cameras are better™ than film. Realistically, they do create better images than film, they shoot faster, focus better, have higher resolution, and capture colors more realistically.

I am obviously a big fan of film. I created this blog to help new film photographers get the best information possible. I’d learned film photography from the forums, where a lot of bad information has proliferated and made me run into mistakes.

But I can’t in good conscience say that medium format film photography is the ultimate photographic medium in terms of image quality. Large format still beats them all through and through. Though, I guarantee that consumer digital cameras will become better over time.

We choose the medium we choose for many different reasons. One reason is the quality of the images we capture and the feel of the medium. And another big one is price. Because even if you can easily afford a new mint condition Leica M6 and a Noctilus lens, that doesn’t mean you could afford a digital medium format camera without remortgaging your house.

What are the downsides of using medium format film cameras?

In this part of the guide to medium format photography, I’m going to give reasons why you probably don’t need or want, a medium format camera. Unlike film, nothing is ever black and white. There will always be more to any decision than just one or two factors.

I’ve had multiple medium format cameras over the years, and they have all served me well. But there are a few real and distinct downsides to these cameras that I have personally experienced.

If you’re looking for reasons to avoid putting your hard-earned money into a medium format film camera, this is the section you will want to read. Let’s start with the cost.

How much does medium format film photography cost?

First and foremost, medium format photography is expensive. A good medium format camera, like a Yashica or Rolleicord TLR (Twin Lens Reflex) will cost between $400 and $500. And the prices only go up from there.

People are picking up these cameras for professional photography uses again, so it’s no secret that the prices are going up closer to where they used to be when film was the only way to take photographs.

When it comes to the film itself, a single roll of color 120 film starts around $10, depending on where you are in the world. Lomo Color Negative film is the cheapest at around $25 for a 3 pack in the US (the cheapest film market), but Portra 400 can fetch $60+ for a 5 pack, or $1 per 6×6 shot.

Fuji, unfortunately, doesn’t make medium format film anymore, so the options have become more limited since 2021.

Developing and scanning film professionally then costs between $10 and $25 per roll, depending on the quality of the scan.

Alternatively, you can do this at home for much cheaper in the long run, but developing and scanning a single roll can take an hour on a good day. Longer if you’re using a flatbed scanner like the Epson V550 or V600.

A complement of B&W film chemicals or a C41 color negative film developing kit will cost around $30. The C41 kit develops 8 rolls, while the B&W chemicals can develop anywhere between 10 and 100 rolls depending on dilution, shelf life, and other factors.

So the total cost per photo varies anywhere from $1.20 on the low end (if you dev+scan yourself) and $3. It doesn’t sound like much, but the costs do add up over time.

In contrast, a roll of 36-exposure 35mm film can cost anywhere from $.40 to $1 per shot. But 35mm film prices can vary far more than medium format.

Are the costs of medium format worth it?

Medium format photography costs significantly more than 35mm. Most rolls of 120 are about the same price as 35mm. though you only capture 10-15 photos instead of 24 or 36. Developing and scanning 120 film also costs the same amount as 35mm

For clients, the mystique around medium format film photography can also be a selling point. As a fashion, lifestyle, portrait, or wedding photographer, you can use the camera to market your work. Some major clothing brands have also switched exclusively to shooting on film to market their clothing as cool or hip.

Is medium format film relevant in the digital age?

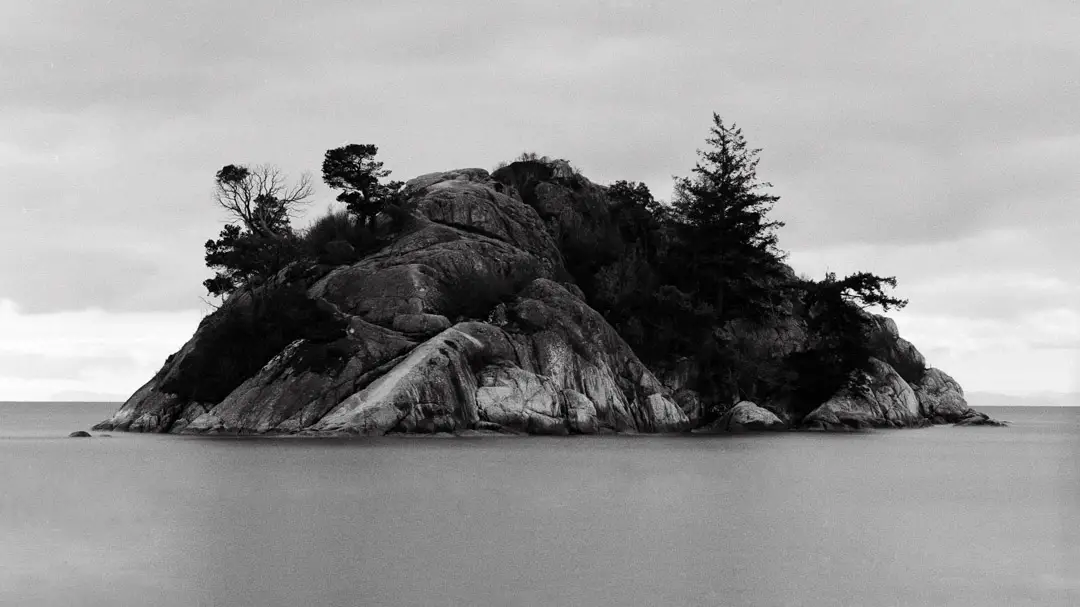

In the digital age, we are limited by the resolution of the scanner and the ways in which we display images online. Large film formats don’t provide that much more detail over a 35mm film scan.

And the reason for that is simple. Most people — photographers and clients inclusive — only want images for Instagram or their websites.

Instagram only requires 2048px wide images at the most or 3 megapixels. On this website, to keep the pages loading fast, I use images that are 1080px in width, which is just 1 megapixel. A well-exposed 35mm film format image can easily cover that space without extra-noticeable grain.

The only time medium format quality matters to me is when I print my images in the darkroom. And even then, I don’t even notice the grain from a 35mm negative on an 8×10 print.

Film options are limited to the highest-quality film stocks

This can be a big factor for many photographers. There are still a large number of high-quality films available for medium format cameras. You can see this list of the 10 best film stocks that will still be available for the foreseeable future.

But there aren’t as many film emulsions available for medium format as there are for 35mm. Part of that is because smaller film producers need to meet the biggest market before they invest in supplying the smaller number of medium-format photographers out there.

But manufacturers are certainly not ignoring medium format. Kodak recently released their famous Kodak Gold in 120 format, and Cinestill almost met the demand to produce their latest Cinestill 400D in the now dead 220 format! So manufacturers certainly aren’t ignoring this section of the film photography market.

Luckily, we still have Lomography, who are taking some of the affordable film stocks from Kodak and making them available for medium format (and even 110).

Getting medium format film developed

Larger film formats are also more difficult to have developed at a lab. Back in the late 90s, there were small film labs popping up in almost every small corner you could find. But they were only developing 35mm color film because it was a standardized process that didn’t need large equipment.

Today the landscape is much different. But there are still labs at some places like Walgreens, Walmart, and Costco — or London Drugs in Canada. But if they exist in those stores, it is usually in a limited capacity. They still mostly only develop 35mm.

For medium format, your best bet is always to go to a more specialized camera store, or to mail the film into a lab.

Scanning medium format

In the digital age, the film type you use is realistically only as good as the digital scan, right?

Having a good film scanning setup at home takes some investment. The easiest way to get started is to use flatbed scanners, which perform much better with medium format than they do with 35mm. They can take a long time to use, but in general, you will get good results with one of these scanners. Find them on Amazon for the best price here.

If you’re shooting both 35mm and 120, and have a digital camera at home I would suggest getting into film scanning with a DSLR. Raw files tend to make converting and editing the negatives much easier than working with the files a scanner will give you.

The only downside to DSLR scanning is that when using a macro lens, after cropping for the right aspect ratio, the film scan from a medium format negative is sometimes smaller than what you would get from 35mm.

This is because a full-frame digital sensor is modeled after 35mm film. In fact, the Sony sensor is wider than Canon or Nikon, because it is modeled to be the most similar to a 35mm film negative.

Once you start scanning larger formats, the first issue that you will come across is finding a scanning mask or film holder that will hold your film negative perfectly flat. If the negative isn’t flat, then the sides of the image will be darker than the middle section, or the edges will be out of focus altogether.

There are plenty of solutions that work well for 35mm, but it is always just a bit more expensive and harder to find a good solution for medium format. I’ve been using the Essential Film Holder for the past year, and have gotten pretty good results with it. But there are always problems when the film has a drastic curl, like when using films with a thin base like Lomo 800.

Darkroom printing with medium format film

Back even 5 years ago, it was easy to find free enlargers online. Everyone was just trying to get these heavy, dusty pieces of equipment out of their basements. It didn’t matter if it was an entry-level machine that originally costed $500 or a high-end $10,000 enlarger — people were just hoping someone would be able to use it.

These days, it’s a little harder to come by. And it’s harder yet to find one that is set up for printing medium format film, which requires longer focal-length lenses, and larger bodies capable of moving further away from the paper.

Medium format enlargers are larger and have longer lenses than 35mm film. Most enlargers will have a 50mm enlarging lens, which is the right size for 35mm. For medium format film you will want a longer focal length lens like 75mm – 150mm.

While you technically can print a medium format film image with a 50mm lens, it will leave lighter edges around your print (much like a white vignette-effect, which you can make in Lightroom Classic or Photoshop). You will also want to stop down the lens 2x from the maximum aperture for the sharpest possible images.

These lenses require a larger enlarger in order to give you enough height to make a good-size enlargement. The larger you want the image to be, the higher the enlarger will have to go. That means many small enlargers on the market will only be able to make 5×7 or 8×10 darkroom prints with medium format film. 16×20 prints may require smaller focal length lenses, like 75mm.

Final thoughts

There are so many reasons why photographers love medium format film photography. I personally have fallen in love with the Hasselblad that I’ve been using for the last year, and haven’t even wanted to pick up a digital or any other film camera since.

But the reality is that just because you have the best camera, doesn’t mean you are going to take the best photographs. Most of the best film images in history were taken on 35mm cameras because of their form factor, ubiquity, and reliability. There are many cases where a small camera just does the trick better.

This is the longest guide I have ever written on the LearnFilm.Photography site. If there is anything specific that you want to know about medium format photography, or about any of the cameras, films, or other details in the article, please let me know down in the comments below.

I love hearing your feedback on my articles, and I do my very best to answer questions as quickly as possible. But you can also feel free to send me a DM on Instagram or post in the growing Official Learn Film Photography Facebook group!

By Daren

Daren is a journalist and wedding photographer based in Vancouver, B.C. He’s been taking personal and professional photos on film since 2017 and began developing and printing his own photos after wanting more control than what local labs could offer. Discover his newest publications at Soft Grain Books, or check out the print shop.

Great and informative article , many thanks for the time and care you put into it