There are plenty of options out there that are all designed for different users. Whether you like rangefinders, SLRs, folding cameras, Twin Lens Reflexes, or system cameras that can be adapted to your every need, there will be something out there for you.

This article is all about going into the different formats and styles that each of these cameras are meant for. Medium format cameras have many benefits over 35mm, in part because of the much larger film format, but also because these cameras were designed to be used for work.

They were the top of the line machines of their time, and were often designed for specific uses. That means there is a perfect medium format camera out there for everyone, no matter what your shooting style is.

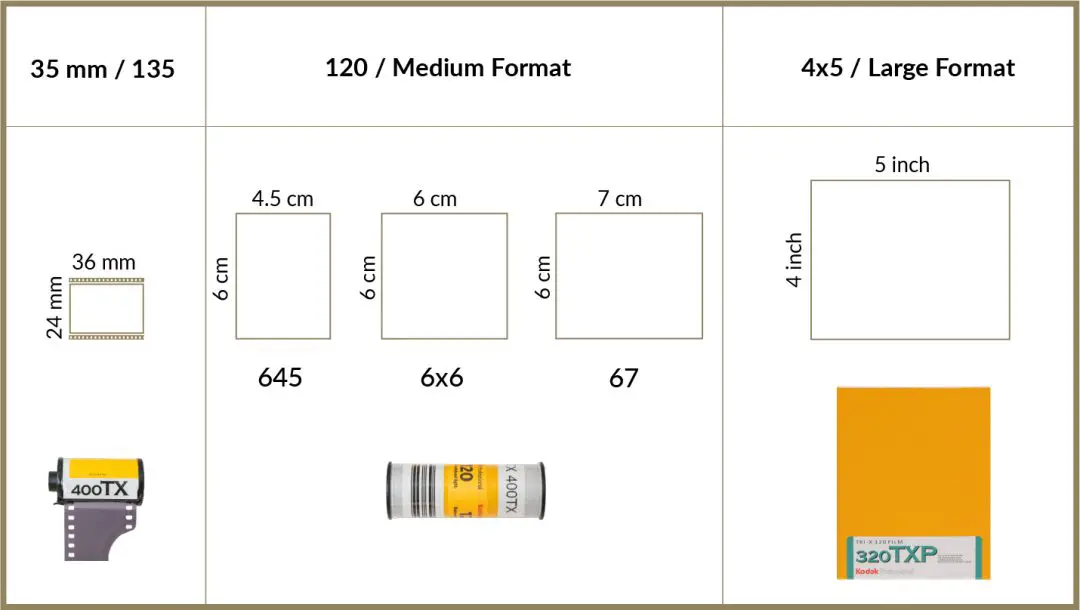

What film formats are out there?

Medium format cameras come in all shapes and sizes over the years, and can also have a number of formats that they shoot in.

The most common formats are 6×45, 6×6, and 6×7 — which describe the centimeters of a single image. For example, a 6×45 camera will take images that take up 6cm by 4.5cm on a roll of film, allowing the photographer to capture up to 15 (sometimes 16) images per roll instead of 12 on a 6×6, or 10 on a 6×7.

The 645 camera was the format of choice for wedding and event photographers who wanted to maximize the quality and number of images they were capturing. So in many cases, there are 645 format cameras out there that feature autofocus, automatic metering, and many more advanced features

6×6 cameras were the standard format. Early Twin Lens Reflex cameras, like Rolleiflex, Mamiya, and Yashica all shot square 6×6 negatives, and the format was then carried forward by Hasselblad in their V-series cameras. Some people love square format, others hate it, because when you print a standard image, you have to crop the square on either the top or bottom.

But most studio photographers went a different route. Since there is more time in the studio and it’s more important to maximize quality, many studio shooters preferred to use 6×7 format cameras, which make images that are 6cm by 7cm on the negative.

The larger format captures about 1.5x as much detail as 645 format, and produces images with a shallower depth of field. But these cameras also tended to cost the most money, and use the most film. Learn more about how medium format works in this article.

Which medium format cameras are the most affordable?

The most affordable medium format cameras are the toy cameras, like the Holgas or the Diana F+ cameras. These are fun, plastic cameras with plastic, fixed-focus lenses, a built-in flash, and no camera settings to fuss with. They usually come with a flash and have a single shutter speed and aperture that works in daylight.

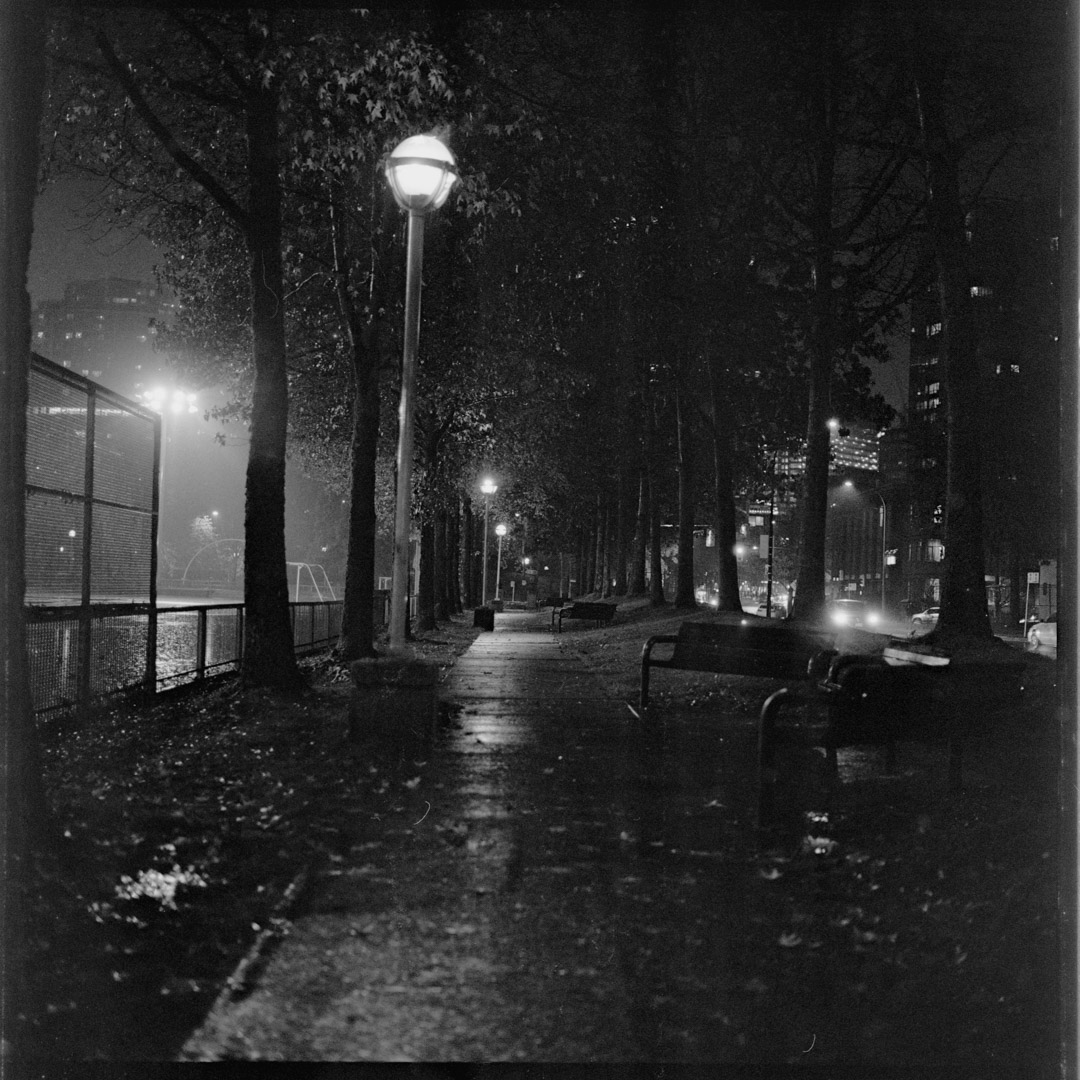

Because of the simple operation, these cameras allow you to only focus on composition. Many photographers, including famous landscape photographers like Michael Kenna have a soft spot for Holga cameras because of the unique look they can create, and how much fun they are to use.

Every Holga or Diana camera will have their own unique quirks, which become very apparent because of the larger film format. Most of these cameras shoot in 6×6 format, but come with an optional 645 mask so the photographer can get 15 shots out of a roll instead of just 12. You can get one of these awesome cameras on Amazon here, or find them at many garage sales and thrift stores for cheap.

If you find a medium format film camera that is less than $40, chances are it uses a format that is no longer sold. Many of them, like most Kodak Brownies, Contaflex, or the cool-looking Kodak Six-20 camera all used 126 film, which is eerily close to 120, but just slightly shorter. To use these cameras, you will need to re-spool 120 film onto 126 film spools.

Are cheaper the Russian medium format copies worth buying?

The Russians made copies of many other famous cameras out there. After being cut off from supply during the wars, the Russians felt they needed to become self-sufficient and created many stunningly-similar copycat designs. These Russian cameras are almost as good as the real deal.

The next step up from these toy cameras are usually the Russian medium format cameras, like the Lubitel-166 LOMO plastic TLR camera (the camera that started Lomography). These are quirky, with all-plastic construction. But they have adjustable exposure settings, a cool waist-level viewfinder, and can be focused so you can create bokeh. All in all, they’re not going to produce the best image quality, but they are fun cameras to use.

On the used marketplace, a Kiev 88 is an affordable copy of the Hasselblad 500 camera system, with almost all of the pieces being interchangeable, meaning you could use a Hasselblad viewfinder, grip, or mount on the Kiev, or Kiev versions on the Hasselblad without issue. The only part that wasn’t interchangeable, unfortunately, is the camera backs.

The Russian copies all do have their quirks, but they’re solid cameras that can create awesome photos. A 500 series Hasselblad will easily set you back around $2000 usd, but a good condition Kiev 88 with an extra back costs only 25% as much, but gives you 80% the same Hasselblad value. Find the Russian copies on eBay here.

If you do purchase one, be sure to take the camera for a professional CLA, and the camera will continue to outlive the USSR. All in all, Russian cameras will treat you well. If you’re looking into medium format on a budget, these cameras are definitely worth taking a look at — especially if you can purchase them in person.

What is a system camera, and who are they meant for?

A system camera is any camera with interchangeable parts that can be changed for your shooting style. These cameras are built around an SLR body, which holds exchangeable film backs, a large variety of focusing screens, prisms (with or without light meters), waist-level finders, bellows, interchangeable lenses, and so much more.

These cameras are loved by professionals because they can be adapted to any style that you choose. Wedding and portrait photographers love them because you can switch between color and black and white film without finishing and reloading a new roll. If you’re shooting fast-paced events, you can preload multiple backs and switch them out at a moment’s notice.

Studio photographers love these cameras as well, because they are reliable, and are designed to create the highest-quality images, and can be adapted to use bellows for closeup photography, or have a variety of mounts that can be added on for flash.

Hasselblad also released a set of lenses, called Super Achromat, that were designed for optically perfect image reproduction (no distortion or vignetting at the edges of the frame on wide-angle lenses) for studio product photographers as well as scientists. These lenses are rare and can fetch prices into the $20,000s today.

System camera prices

And not all of these cameras are expensive. There are, of course, the famously expensive Hasselblad 500 series cameras, the Mamiya RB or RZ 67, and Contax 645 camera systems. These cameras are absolutely worth their prices — especially the fully-mechanical bodies that are easier to maintain and repair.

Most of the higher-ticket system cameras, like the Hasselblad 500 series, and Contax 645 system cameras are expensive. They come in around the $2000+ mark for the camera with a kit lens and film back.

But there are also much more affordable cameras, like the Zenza Bronica ETRS and ETRSi that seriously punch above their weight for the price. The lenses are tack sharp (and cheap!), and the systems work extremely well. Of course, with more electronics does come more problems. But overall, these cameras are dependable, and they were the wedding photographer’s dream camera in the 80s for a reason.

But there are also options, like the legendary RZ67, a 6×7 format studio professional camera, that can be bought for $700+ as a kit, with later models costing over $1000 (find them on eBay here). The larger, 6×7 size negative (and rotating back) is something many photographers love to have for studio photography. But don’t expect to take this camera up a mountain — the camera body alone weighs 1.4kg. Add a lens and back will, and the RZ67 easily weighs over 2.5kgs!

What is a TLR camera?

A TLR, or Twin Lens Reflex cameras are small, portable, and vintage-looking cameras. At first sight, these don’t look like anything you’ve ever seen. TLRs have two lenses — 1 lens for viewing the image, and another one just below it for taking the image. These cameras use a waist-level viewfinder and take images in a square 6×6 film negative.

TLRs became popular in the 1930s because of their reliability and ease of use. The form factor was great for street photographers who used the unassuming style of this camera to take sneaky street photos. The lenses on these cameras are also ridiculously sharp for their age.

With a camera like this that sits around your neck, it can be difficult to know if it’s pointing at you. So people on the streets seem much more comfortable around these cameras — at least in the modern age.

Most Twin Lens Reflex cameras have fixed lenses, and focus by moving the lens back and forth on a board, like the popular Yashica and Rollei cameras. The Mamiya C330 is the only TLR that can actually exchange lenses, though it has a much larger and heavier form factor.

Unfortunately, most of these cameras are becoming quite expensive because of their growing popularity. The cameras are also difficult to repair even though they are fully manual. The leaf shutter mechanisms are difficult for repairmen to access and are known to struggle with age.

The Mamiya C330, however, still remains fairly affordable, despite having interchangeable lenses.

The Yashica Mat 124 was my first film camera. I took it with me everywhere and got some really incredible images with it. The bright focusing screen made focusing easy, and the form factor of the TLR camera makes getting steady shots at slow shutter speeds surprisingly easy.

Learn more about TLR cameras in this in-depth LearnFilm guide.

SLR versus Rangefinder medium format cameras

There are two main types of medium format cameras: SLRs and Rangefinders. These two systems are completely different from one another, and both have their own benefits and drawbacks.

SLR stands for Single Lens Reflex. SLRs have a through the lens viewfinder so you can see exactly what the camera sees — including depth of field. They are accurate and quick to focus. SLRs have been the backbone of professional photography because of these benefits.

But SLR cameras do have a mirror that they have to move out of the way before the image can be taken. The mirror often moves extremely fast so the photographer can capture the decisive moment. But the problem is that these mirrors are loud and can also cause some amount of shake in the images.

For long exposures, the shake will be small but it will make the image noticeably less sharp. The alternative is to use mirror lockup. However, that mode prevents you from being able to see through the lens. The last issue is that an SLR viewfinder is only as bright as the lens that is on the camera. That means it can be difficult to focus your image at night when using a slow lens, like an f/5.6.

Most cameras, including every system camera, are SLRs because of their dependability. They don’t need to be calibrated, and they’re typically really good at what they do.

Rangefinders have a focusing system that is uncoupled from the lens. When you look at these film cameras, they will have two screens — one is the main viewfinder, and the other has a focusing patch. When you focus the lens, there is a little lever inside the camera that gets pushed, controlling the position of the focusing patch in the camera.

The benefit of the rangefinder system is that it is simple to use. You can tell quickly when something is in focus (so long as the camera is calibrated). These cameras also don’t have a loud mirror to move out of the way with every exposure, making them a favorite for street photographers everywhere.

The downside of a rangefinder is that the focusing screen is not coupled to the lens, meaning you don’t actually know what the film is going to see. Most viewfinders have a 30mm field of view, and some of them have frame lines that show approximately what the frame of your image is going to be.

Close-up portraits, do, however, suffer from parallax error, where the image is taken from a lower angle than it looked in the viewfinder. Parallax error is especially bad with long focal length lenses.

If you’re someone like me who enjoys using long, telephoto lenses like 135mm or 85mm, then these cameras can be difficult to know exactly how your image is going to look. As well, the focus on those lenses needs to be more precise. So most rangefinder photographers stick with 35mm.

Because of these downsides, there are only a handful of medium format rangefinders. The most common one is the Mamiya 7 and 7II. These are some of the most sought-after medium format cameras on the marketplace, fetching a premium price of above $3000 USD. A more affordable option is the Fujifilm GA645. However, those cameras only use one lens that is fixed to the body instead of interchangeable.

Final thoughts: What’s the best type of medium format camera for beginners?

If I had to do it all again, I would definitely start out with a TLR camera again. If you find a good one, like a nice Yashica A, or Mat-124 in good condition, it’ll be the kind of inspirational camera that helps you get outside and learn how to shoot film like a pro.

The Yashica cameras have very sharp lenses, allow you to take awesome street photos, and are the kind of show pieces that people can’t help but get excited about. The waist level viewfinder can be tough to use at first, but it becomes second nature in time. Find your perfect Yashica TLR in good condition on eBay here.

The next camera that I’d push new medium format photographers towards is the Mamiya RB67 system camera. The camera might be heavy as heck, but it’s an all-mechanical dream machine that is perfect for using in the studio. The lenses are tack sharp, the rotating back makes it easy to get portraits and landscapes, and the bellows make it an absolute dream to get those up-close photos that turn heads.

No matter what camera you choose, medium format is so much fun.

By Daren

Daren is a journalist and wedding photographer based in Vancouver, B.C. He’s been taking personal and professional photos on film since 2017 and began developing and printing his own photos after wanting more control than what local labs could offer. Discover his newest publications at Soft Grain Books, or check out the print shop.